I´m not discovering fire if I say that, in order to understand the present, there’s nothing like a little digging into the past and learning from the unique perspective that only the simple and natural passage of time can bring. And this is precisely what today’s lines are about.

With the First World War barely over, Berliner architect Walter Gropius, decorated for his participation in it, founded the Bauhaus school in April 1919 in the German city of Weimar. Influenced by his experience of the conflict and his vision of the world, he believed that the new society that was to emerge after the war would require a new kind of artist, one who would explore the intersection between craftsmanship and industry, thus blurring the horizons and barriers that then existed between the different artistic disciplines. With the creation of the school, in which architects, craftsmen, painters, carpenters, actors and actresses, sculptors, typographers and photographers participated as teachers and pupils, Walter sought to lay the foundations of the pedagogy for this new profile of the integral artist.

In 1925, the school had to move from conservative Weimar to industrial Dessau, and Gropius itself was in charge of the design of the new building, as well as the Master Houses that would host teachers and their families.

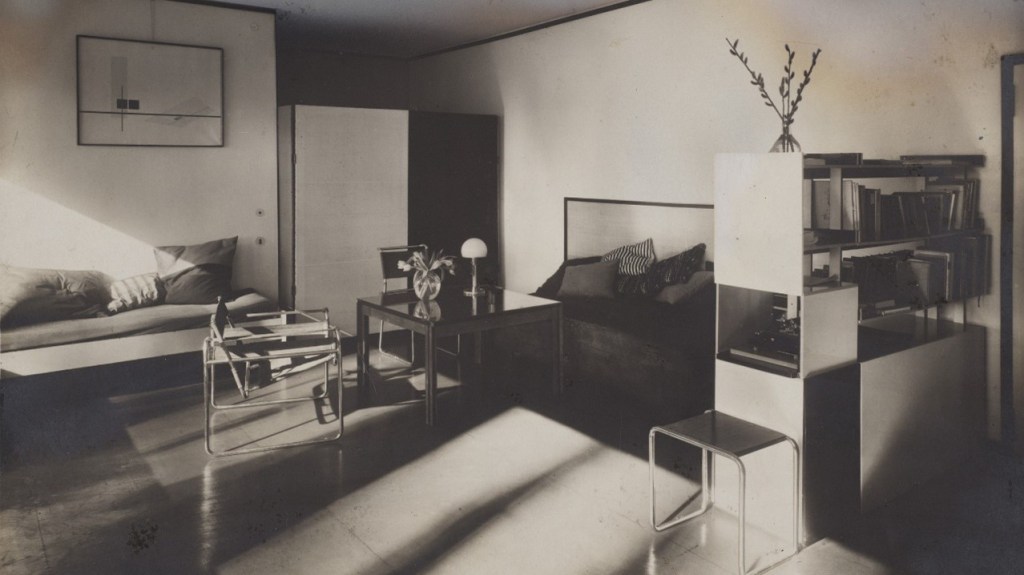

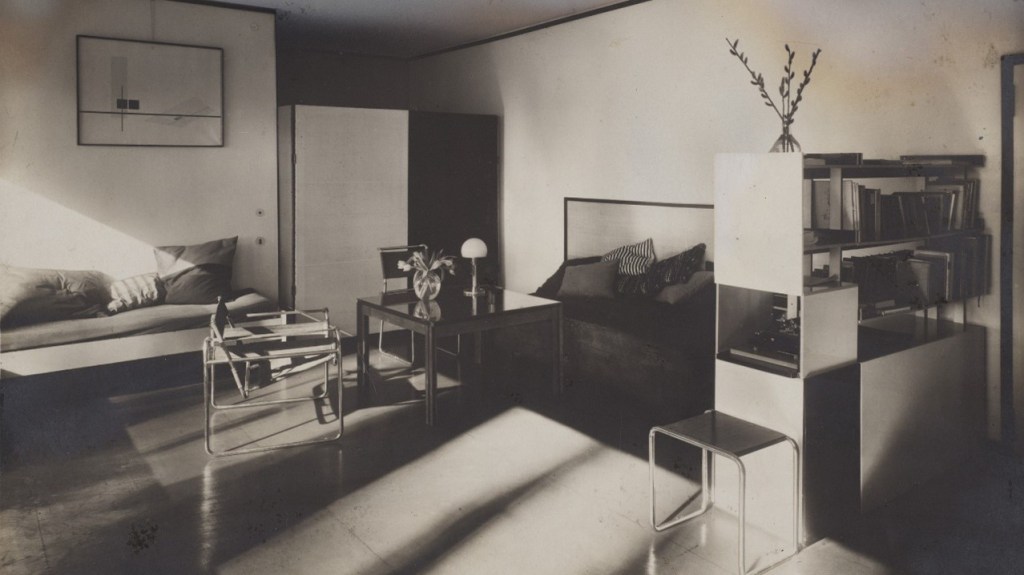

To try to unravel how the legacy of this movement, born more than a century ago, has come down to us today, I invite you to take a closer look at the photograph that opens today’s letter:

Apparently, it´s a a rather austere corner without much complexity, isn’t it?

The space in the photograph corresponds to the living room of the married couple, the Hungarian-born professor László Moholy-Nagy and Lucia Moholy, a Czech writer and photographer who, between 1923 and 1928, was officially responsible for immortalising the life, spaces and projects of the Bauhaus. The image, as the credits state, is hers.

As well as working to emulsify industry and craftsmanship, one of the founding principles of the Bauhaus was to make design accessible to the greatest number of people (excerpt from the last paragraph of the Bauhaus manifesto):

“Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come..”

Therefore, mass production of objects in order to reduce costs and reach a large number of households was a premise that was always kept in mind during the creative process at this school. The Moholy living room, for example, features tubular steel furniture by Marcel Breuer.

Breuer, trained at the Bauhaus, also served as a teacher in the cabinetmaking workshop. He used to use the bicycle as a means of transport, and this must have inspired him to create the B3 model, also known as the Wassily armchair, the first tubular-frame armchair with a leather seat, armrests and backrest, present in the Moholy’s Master House, but also an icon of modern design today:

In addition to industrial production as the key to the democratisation of good design, Marcel Breuer was aware that, in the modern world, things were changing at a faster pace than had been known in previous decades. It was therefore important for the design of spaces and furniture to be flexible and modular, so that they could adapt to the constantly changing needs and demands of people, and not the other way around. Another representative example of this vision is the small piece of furniture on the right-hand side of the photograph, which in this case served as a stool for typing, but could also be used as a side table. This piece of furniture, which is part of the B9 or nest series, as well as being made of tubular steel, had the advantage of being stackable together with its ‘sister’ pieces of smaller or larger size, thus saving space when necessary:

During the same period, the German artist Josef Albers, artistic director of the school’s furniture workshop between 1926 and 1927, designed a similar concept, with a wooden variant and making use of the Bauhaus’s characteristic colours, the primary colours red, blue and yellow:

Later, and outside the context of the Bauhaus, although certainly influenced by it, Alvar Aalto also worked on the concept of stackability, in his case, applied to stools, creating the more than famous model 60, with three legs and a circular seat, which has been manufactured in birch in Aalto’s native Finland since 1935:

Moving on to lighting, the MT8 lamp by William Wagenfeld and Carl Jakob Jucker, designers of German and Swiss origin respectively, can be seen above the dining table. Also known as the Bauhaus lamp, it became the epitome of another of the school’s principles, ‘form follows function’. Constructed in steel and metal, its simple geometry also made it an easily industrialised product that is still in production today:

Given that the Bauhaus developed as one of the fundamental arms of the modern movement, another aspect worth highlighting is the use of natural light as a modulating element of space. The liberation of the wall as a structural element, as well as making it possible to design open-plan domestic spaces (which we love so much today), allows large windows to be opened to let in natural light and blur the interior-exterior barrier, with nature, as well as light, becoming an element of interior design.

In the Moholy living room, we can see how natural light enters almost to the wall, and we imagine that the two sofas or daybeds are strategically placed to observe from them the trees of the pine forest on which the Dessau Master Houses were built; the two vases with fresh flowers (dining table) and dried plants (shelf on the right) corroborate the celebration of nature in domestic spaces, something present in many of our homes in the 21st century.

Although at first glance the black-and-white photography salon may not appear to be of any particular interest, a closer look reveals it to be a true example of both the modern movement and the Bauhaus philosophy. Designing is a whole. Nothing is separate any more; everything has a reason to be and works together. Light, nature and furniture as structural elements of the interior space, the elimination of the superfluous, the relationship between interior and exterior, the human dimension, the resolution of needs above aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake. Functionality. Democratisation. A whole series of values that have survived the century of life and that today seem more necessary than ever.

Happy saturday; love a lot.

Thanks for reading

Deja un comentario