RefugioNorte was born a year ago with the intention of reflecting on the capacity of the spaces we inhabit to provoke emotions and shape our behaviour. Although each edition of RefugioNorte contains a little bit of this, today we explore a terrain that delves deep into the subject.

In 1994, a guy named Jeff opened an online shop in Seattle to sell books. A year later, he launched amazon.com: in his first month, he sold books in more than 45 countries. What came after that is common knowledge.

Throughout these three decades, some out of conviction, others out of necessity, consumer brands have been launching themselves into the digital channel as an indispensable means of invoicing. At the same time, Amazon, as well as being a pioneer in e-commerce, has laid the foundations of what we shoppers expect (demand!) during our digital shopping experience: reading other people’s opinions, one-click shopping, easy, no-questions-asked returns and instant delivery.

The power of the digital channel seems unstoppable and, in this context, brands are questioning the role of their physical shops in their omnichannel strategies, those that integrate physical and digital touchpounts, with the aim of offering those who are going to spend their money something that they cannot find in their .com space.

If the internet offers maximum convenience, minimum friction and I have at my fingertips all the information about the product or service I am interested in, why would it be worth my scarce time and valuable attention to go to a shop with an entrance door and product display furniture? What can brands do in their physical spaces to increase my affinity for them and make me want to spend more? Well, what good brands have always known how to do: seduce us.

Seduction is a strategic pillar in branding because it allows brands to connect emotionally and build long-term relationships with the public in a context full of stimuli and in which the immediate is the priority; it is not about capturing our attention for the sake of it, but about generating desire, differentiation and trust. And now that we spend much more time glued to our screens, getting fine-tuned with audiovisual content than we do bonding with the physical world for which we are evolutionarily designed, brands that know how to seduce us by appealing to all our senses will have a competitive edge.

In the words of communication strategy expert Cecilia Rodríguez, from Proyectario studio:

«The most lucid brands understand that if they do not recover the world in which something can be felt and preserved, we will gradually fade away».

The most lucid brands understand that, if they do not recover the world in which something can be felt and preserved, we will gradually fade away. And without presence, there is no link.

In the conception of a seductive, pixel-free experience that makes us connect with the DNA of a brand, architecture and interior design applied to retail play a primordial role because, when well executed, they have the capacity to convert physical spaces into a tangible extension of the brand’s identity and values with a clear goal: to captivate us in the short term and build loyalty in the long term.

If brands want their shops to be a place where more than a mere transaction of goods (your money for my product) happens, their interior has to be anything but banal; brands that know, know the importance of this. And today we take a first look at some of the symbiotic relationships between brands and architects that have managed to create retail spaces that are another expression of the brand essence and in which everyone has come out a winner:

1 / Le Bon Marché, París

Louis-Auguste Boileau

Le Bon Marché, still a landmark in the French capital today and officially opened in 1852, began life in Paris in 1838 as a haberdashery run by husband and wife team Aristide and Marguerite Boucicaut for fabrics, sewing accessories, umbrellas and bed linen. However, they quickly spotted an opportunity to create a new type of shop that would engage all the senses and transform the shopping experience into something pleasurable and accessible. With the help of French architect Louis-Auguste Boileau, a pioneer in the use of metal structures, they opted for a large, bright and elegant space where customers could explore freely, touching and tasting the products as they pleased, something unheard of in the mid-19th century. Not content with this, they introduced commercial practices that we take for granted today but were not then, such as fixed prices, mail order, home delivery and return policies, as well as cultural events and private concerts, thus becoming the first Parisian department store. In other words, the Boucicauts’ ambition was to create a revolutionary retail space that was both functional and seductive.

Among the innovations applied in terms of architectural space, the use of the iron and glass structure, which made it possible to conceive large open-plan spaces bathed in abundant natural light, stands out. Later, in collaboration with Louis-Charles Boileau and the engineer Gustave Eiffel on the extension work, Le Bon Marché became an international reference point for both its functionality and its aesthetics, inspiring other galleries such as Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan (1867) and the Carson, Pirie, Scott & Company department store in Chicago (1899-1904), the latter designed by Louis Sullivan, the father of modern architecture and the architect of the reiterated ‘form follows function’.

In short, Le Bon Marché, still in operation today and owned by the LVMH group, was a visionary project that combined an innovative retail offer with advanced, elegant, quality architecture that forever transformed the shopping experience.

2 / Calvin Klein, New York

John Pawson

In the early 1990s, when minimalism was establishing itself as a dominant trend in fashion, design and art, Calvin Klein was one of the most influential American brands in the market, renowned for its minimalist aesthetic, iconic advertising campaigns and its ability to turn basics such as jeans and underwear into objects of global desire. In this context, the brand was looking to consolidate its image of contemporary, sophisticated luxury, and needed its flagship space in New York to reflect these values.

British architect John Pawson, though relatively emerging at the time, was already known for his radically minimalist approach and sensitivity to light, materials and space. Calvin Klein himself was smitten after visiting Pawson’s Notting Hill home in 1993, where the architect applied an extreme simplicity inspired by Japanese culture and monastic architecture, even concealing furniture in built-in cabinets. This vision of a ‘place of worship’ and spatial purity fitted perfectly with the image the brand wanted to project, as Klein aspired for the shop to be an architectural manifesto, an almost sacred space where the product was the absolute protagonist and the environment fostered a sensory experience of calm and refinement.

In Pawson’s words, Klein was looking for:

…a shop that would create the conditions in which people would feel good about spending money. He wanted an environment that didn’t feel ostentatious or too luxurious, so that people wouldn’t feel guilty. Klein turned the idea of modernity into his own clothes, austere and simple, but sensual and confident.

After closing the deal for the creation of the brand’s first own shop in New York and thinking long and hard about how far they had to move away from the conventional but without forgetting that whatever they conceived had to work on a commercial level, Pawson designed a space with large surfaces of York stone, impeccable white walls and minimal furniture, achieving an atmosphere of serenity and monumentality that revolutionised the design of flagship shops in the decade.

The new store opened on Madison Avenue in 1995 and was seen as a ‘temple’ of minimalism, marking a before and after in commercial architecture and consolidating the international reputation of both the brand and the architect himself. The shop had 2,050 m2 distributed over three floors, the first of which had 9-metre high ceilings. To be consistent with the concept of minimalism, Pawson proposed to Klein that the windows in the façade should be of a single pane, covering both the first and first floors, and so glass panels were designed to be 10.3 metres high by 3.5 metres wide, the largest size that the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, the supplier at the time, could build. To install the windows with cranes, Madison Avenue was closed for four consecutive weekends.

As a result of the Klein-Pawson collaboration, nine more shops have opened around the world, and when Klein celebrated the 40th anniversary of the brand’s creation with an event on the High Line in 2008, John Pawson designed the installation. The New York shop was open for almost 25 years.

3 / Aesop

Multiple studios

The name Dennis Paphitis may not sound very familiar. But if we’re talking about the Australian cosmetics brand Aesop, whose iconic, drugstore-look soap packaging has flooded the editorials of every architecture and design magazine of the last decade, it might ring a bell. Paphitis was born in Melbourne in the 1960s to a Greek family who ran a barbershop on the outskirts of the city; drawn to the world of cosmetics and personal care as a child, he trained as a hairdresser and opened a salon called Emeis in 1987. In this setting and driven by his restless spirit, he began experimenting with the use of essential oils with the aim of creating effective, pleasant and gentle hair products that he tested on his own clients.

This was the germ of what we know today as Aesop, a name chosen as a nod to the Greek fabulist Aesop, a symbol of timelessness, to distance itself from the grandiloquence of cosmetics that dominated the market in the 80s and 90s. From the outset, the brand’s philosophy was based on the values of honesty, humility, ethics and quality, which made coherent, for example, the choice of using pharmacy bottles to sell its ‘potions’ (and which today is copied by so many brands). With this mix, Aseop has become a global cult cosmetic brand, with high quality products, its own aesthetics, sales exceeding €500m and which, despite its appearance as an independent brand, has been part of the portfolio of the giant L’Oréal for years.

The first Aesop shop opened in the Melburnian suburb of St Kilda in 2003. Soon after came the city centre shop, another shop in Taipei and, in 2008, it was Europe’s turn, with the first shop in London, conceived by British designer Ilse Crawford. Today, Aesop is present on all continents through its more than 400 points of sale.

I will never forget the first time I tried an Aesop product; living in Melbourne in 2013, my friend Garth gave me Resurrection Aromatique hand cream and I was fascinated by the smell, the texture and the packaging itself. When I returned to San Sebastian, I discovered that the only point of sale in Spain was in the Urbieta perfumery in San Sebastian. Beyond the anecdote, how to transfer the intense sensorial and aesthetic experience of using Aesop products to a physical space? And how to do it, moreover, by giving each shop a context of the place where it is located, to avoid the clientele having that disappointing feeling that, having visited one Aesop shop, you have visited them all, as happens with the majority of stores belonging to large groups? How to be global and recognised without seeming to come out of the same mould? To answer this question, as Aesop experienced its international expansion, Paphitis began to work in each city with different architects, both emerging and established, prioritising the use of local materials. In this way, it has managed to give each of its shops a local and distinctive touch, but without losing the Aesop essence, which is immensely rich on a sensorial and aesthetic level.

Despite this sought-after heterogeneity, how do you capture that essence in all your shops? I try to summarise it in five points:

1 / Contextual design: Each shop is conceived as a response to the local context, honouring the architecture, history and identity of the place where it is located; the genius loci or spirit of place that we have already talked about in other editions.

2 / Spatial functionality: The spaces are practical and clear, with simple furniture and a layout that facilitates navigation and the visitor’s experience.

3 / Noble materials: Local, noble and high quality materials are used, such as wood, stone, marble, brick or ceramics, which have a patina, age well and transmit authenticity.

4 / Sophisticated minimalism: A clean, minimalist style predominates, which does not overwhelm, but with a high level of detail and sophistication in materials and finishes.

5 / Sensory experience: Aspects such as lighting, aroma, sound and texture are carefully considered to create an enveloping and memorable atmosphere that invites to the ritual of self-care.

In addition to the aforementioned Ilse Crawford, the list of studios Aesop has worked with includes names such as the Norwegian Snøhetta, the Brazilian Paulo Mendes da Rocha, the French Ciguë and the Australian March Studio. As it would take several volumes of a book to talk about all of them, we close today’s edition with the project by the Barcelona studio Mesura for the shop on Avenida Diagonal in Barcelona which, in addition to the focus on local identity, brings a layer of sustainability to the project in the form of reuse of materials.

Mesura for Aesop Diagonal, Barcelona

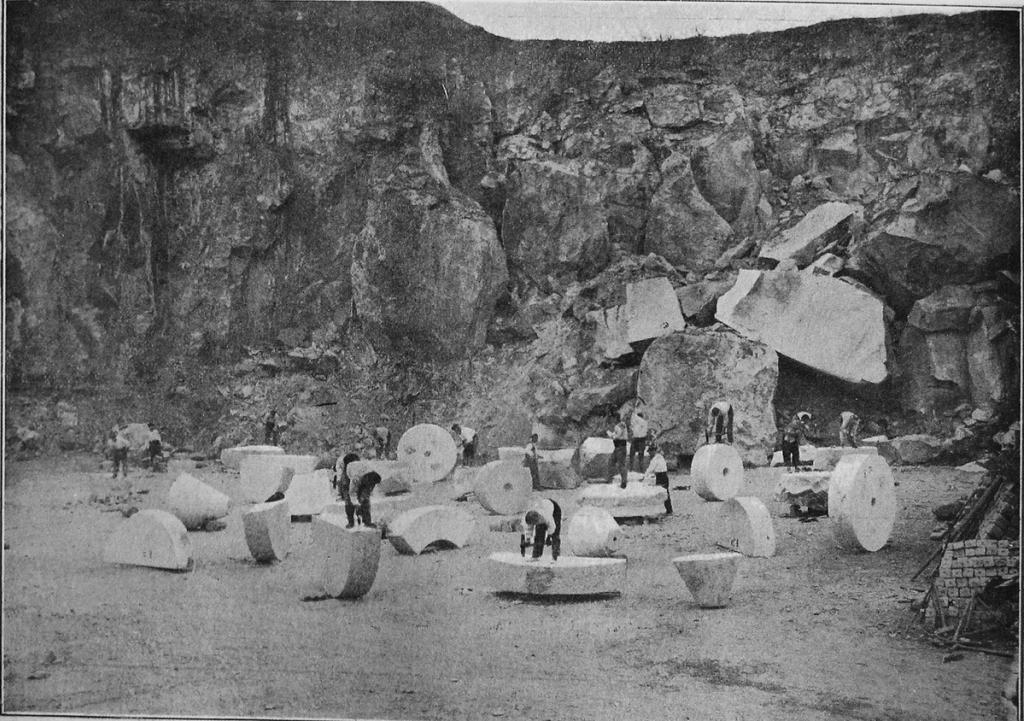

In order to come up with a concept that focused on the social atmosphere, Mesura conducted a study on the history of public fountains in Barcelona. This study led to the conclusion that the stone from the local Montjuïc quarry was, in terms of quality and suitability for the project, the material on which they should focus. Due to its scarcity, this stone is no longer quarried, but it was highly prized for its strength and colour and was used in the construction of shops and historic buildings in Barcelona for centuries.

In a parallel story, the Barbany family, owners of the quarry, spent decades collecting this stone from spaces that had been demolished. When they found out what Mesura was up to, the Barbany family offered the stone archive to the project.

Thus, Mesura made a selection of 78 stones rescued from what were once fountains, plinths or other singular spaces in Barcelona, all of them different in shape and size, and designed the space from them, assembling each stone in a handcrafted and precise manner in the shop itself.

The result is a space that balances density and subtlety, yesterday and tomorrow, in which the stones, the protagonists of the space together with the Aesop product, are integrated into a neutral and functional environment finished in textured stucco, which contrasts perfectly with stainless steel taps and shelves.

Although the subject matter goes on for a long time, I hope you liked this first foray into the design of shops and how, although it is not the norm, it can be enriching for brands, the streets of our cities and us, the public, the conception of commercial spaces that dialogue with the environment, using local materials and based on an architecture that invites exploration and discovery, seducing us and inviting us to leave the house and park for a few hours the bottomless burrows we can get into when we get ready to buy on the internet.

I say goodbye until September to spend the summer days resting from screens and clocks, spending a lot of time appealing to the senses close to nature and losing myself in that world where, as Cecilia says, things can be touched and preserved.

I wish you a happy Sunday and a joyful and very sensory summer,

Deja un comentario